Wednesday, October 30, 2013

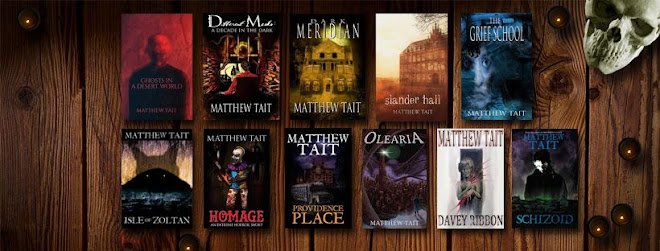

GHOSTS IN A DESERT WORLD ON SALE TODAY

As you can see from the original manuscript, this is a collection that has been whittled down over time to encompass only the best prose and stories.

For the first time in paperback, GHOSTS IN A DESERT WORLD on sale from Amazon now.

Saturday, October 26, 2013

Monday, October 21, 2013

The Last Night of October by Greg Chapman

It’s no secret I’m a fan of what Greg Chapman is doing here in Australia. Although his written works are in a developmental stage, he has proved himself quite the renaissance man by tackling the art world with pencil and brush stroke alike ... an endeavour recently peaking with himself, Lisa Morton and Rocky Wood taking out top honours for superior achievement in a graphic-novel at this year’s Bram Stoker Awards. More than his list of accomplishments, however, is an individual who genuinely cares about his chosen fields. Earlier this year, Bad Moon Books saw fit to acquire his Halloween novella The Last Night of October. Featuring illustrations by the author himself, this is the sort of quick, deep and biting novella we’ve come to expect from Greg.

Confined to a wheelchair, Gerald Forsyth is ill of health and in the twilight of his life. He has many concerns ... but chief among them is Halloween night. What he fears the most is not the exuberance of the annual holiday from a crotchety old man’s point of view. No, Gerald’s phobia is rooted in supernatural dread – for Halloween is the one evening of the year when a very special trick-or-treater comes knocking at his door ... a boy from his childhood past who wants something from Gerald; perhaps atonement for past transgressions, perhaps his very soul. When a relief nurse of Gerald’s accidentally lets the boy inside, the two of them hide within the house. And it’s here that Gerald must recount his story, not only to be relieved of the burden of his guilt but of the very tale itself.

The premise is a simple one – reminiscent perhaps of Greg’s earlier novella The Noctuary. In that particular story, similar motifs were on display: childhood secrets, sins of the past, and present day retribution. Here, however, they have been infused with the glamour and cavalcade feel of Halloween. In regards to this, Greg’s descriptions have already earned approval from American audiences (it’s common knowledge Halloween is not overly celebrated on Australian shores). The carnival feel is present and so is the nostalgia inherent in a young boy’s life – that time of adolescence when ones imagination is never riper and monsters take centre stage with love. As Gerald recounts his tale, a different sort of monster eventually steals the limelight, giving the author a chance to add even greater depth by treading the path of life’s choices and their consequences.

However, this is not a work without some minor errors, and a reader may feel themselves taken aback when a phrase or word is sometimes repeated within a page or paragraph. An example of a sentence that could be easily adjusted:

His chest rattled and Gerald felt blockage within his chest.

Though somewhat of a pet-peeve, I’ve always found repeated words to be a hindrance to coherent flow, giving the reader a self-conscious awareness. There is also a generous heaping of adverbs on display ... although the jury is still out with regards to their legitimacy overall in popular fiction.

Small mishaps aside, this genuinely is a delightful book – one for all ages. Rich in metaphorical writing with an aside of aching nostalgia, The Last Night of October is Greg Chapman right at home and in his element.

Saturday, October 19, 2013

809 Jacob Street by Marty Young

In this particular stanza of a review, I will usually give a mini-lecture about the author under our microscope: how she or he fits into the landscape of dark fiction etc.etc. For Australian Marty Young, I won’t go into too much detail – but suffice to say we have an author who has been at the forefront of Australian horror for quite some time ... and I don’t mean publishing (although he has been partaking of that also). No, Marty’s time has been devoted to the shadows; working tirelessly behind the scenes to build a community that was somewhat non-existent in its current incarnation less than a decade ago. By giving genesis to a small cabal that would ultimately become the Australian Horror Writers Association, Marty changed the landscape of Australian horror in perpetuity - providing starved writers here a much-needed voice on the world stage. And he did this, of course, while tinkering away on his own novels. When the small press Black Beacon Books sprang up a short time ago, it seemed like the perfect time for Marty to release his debut novel ... pairing him with a publisher well-versed fiction and equally enthusiastic about the genre.

809 Jacob Street introduces us to Joey Blue, a resident vagrant of Parkton. (Think Castle Rock or any other fictitious town). Joey is an old bluesman who wanders the borderlands of his town, never quite figuring out if he is actually alive or a ghost himself. Blotting out the past with heavy drink, Joey is paid a visit from an old friend who requires help - whose disappearance years ago is tied to the house on 809 Jacob Street: a rambling old structure which has seen its fair share of death and stands like a testament to the ultimate haunted house.

Across town we Byron James, a young Australian recently moved to Parktown. Adapting to small town life after Sydney is hard ... especially with his new friends Ian and Hamish – both of whom are into the macabre and have an overt obsession with the house on Jacob Street. After Byron’s personal research into the house’s past fails to yield sufficient information, a journal falls into his hands. And then, when Ian proposes a night journey to find out some answers for themselves, it seems like a perfect yet dangerous plan.

Although aware of Marty’s work previous, I came into 809 Jacob Street almost completely cold and without the vaguest notion of what to expect. Sure, both of us have grown up on a rich and steady diet of Stephen King – but I wasn’t quite prepared for how proficient this little novel turned out to be. Evoking those stories of old with his motley crew of kids (1980’s horror fiction), Marty gives the reader a subtle coming-of-age tale while also delivering cerebral prose that becomes almost narcotizing after a while. Here, there is a slow build of tension that is somewhat effortless ... as if 809 Jacob Street was a latter novel in the author’s resume. Also interspersed within the story are small, hallucinatory images from artist David Schembri keeping within the guidelines of restrained horror while complementing the prose. If I had one gripe with the tale as whole, it was having the author unceremoniously pull a character at the midway point without them having any real influence in the final act. Like a series of intersecting dominoes, the two-plot strands failed to align in a coherent manner – a small blight in an otherwise consummate tale of dark fiction.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

THE CHILDREN

Evil, malign children as the focal point for a

horror premise. Let’s reel off just a few of them, shall we? There are outings

such as The Exorcist and The Omen, of course – retro masterpieces

that have stood their ground over the span of generations. Different

incarnations of Village of The Damned

and vintage classics like The Bad Seed.

For modern audiences, there is the memorable performance by Gage Creed in Pet Sematary. And, in horror literature,

Stephen King laid out some of the early foundations with Children of the Corn ... a

small, dark slice of rural Americana that has spawned an entirely unremarkable franchise. What all of this tells us, of course – is that little

monsters in the genre are here to stay. When the most innocent of our creatures

in the human tribe succumb to a malady of evil, wide-eyed disbelief is often

tempered with guilty pleasure. As the children go about enacting revenge on their oppressive

adult overlords, it’s occasionally all too easy to root for them.

Released in 2008, The Children is a British horror film that found approval on its native shores but has largely gone under the radar elsewhere. Here, the writer's have taken a well-worn sub-genre (creepy kids), but found a relatively original plot for them to navigate around. Though an unexplained virus seems to be at the crux of the narrative, the story is lent strength by its isolated setting, domestic component, and a slow build of tension.

Released in 2008, The Children is a British horror film that found approval on its native shores but has largely gone under the radar elsewhere. Here, the writer's have taken a well-worn sub-genre (creepy kids), but found a relatively original plot for them to navigate around. Though an unexplained virus seems to be at the crux of the narrative, the story is lent strength by its isolated setting, domestic component, and a slow build of tension.

Snow is thick on the ground when Elaine

and her family (husband Jonah, teenage daughter Casey, and two younger children), arrive to spend Christmas and New Years with her sister Chloe and her own

extended family. It’s a picturesque occasion ... not only having relatives under

one roof for the festive season but doing so in a country environment quintessentially

British: a holiday of fire, hearth and snow. Laughter is prevalent, and the

decorations have been hung. Soon, family members begin exhibiting strange

symptoms: some of the children are vomiting and becoming listless; emo teenager

Casey merely wants to escape. Random acts of playtime in the snow turn

malicious with deliberate acts of sabotage intended to hurt the adults.

Misbehaving children, crying children, and a general air of malaise (beyond the ordinary holiday norm) all culminate in a gruesome fatality: the demise of an adult in a

contrivance that is anything but an accident. Although the authorities are

alerted, the snow and isolation delay a response, giving the children more than

enough time to form an unruly cabal ... and play the adults off to their ultimate

demise.

Though the catalyst for the children’s

decent into madness is never properly addressed, its very enigma makes their motivations ultimately more appealing. With no rules or strictures,

you never quite know what to expect or what palpable spooks lay in wait – a

refreshing change from a decade of horror where ‘nothing we haven’t seen

before’ becomes a ritual critique. By the mid-point, a lot of confusion abounds

– not just for the terrified adults, but for the viewer who now has to contend

with second-act filler: moody looks from our teenage emo, over-acting, and

awkward dialogue. Fortunately these small, self-conscious scenes do not

over-extend themselves, making headway into a third act that amps up the

carnage and doesn’t overly censure itself.

Low on gore but still potent in

atmosphere, music, and pacing - The

Children is reminiscent of some of the more memorable films of the eighties

– albeit with a far lower budget. (With all that snow, The Omen II sprung to mind on more than one occasion). Performances

from the children are mature, and overall the film stretches its rating by

daring to splice them with unrestricted savagery. The ending, when it arrives, is

one the finest elements here. Not a twist per se ... more a final ‘coda’

that raises more questions and leaves the door open for added

mythology.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)